History of Tapestry - technical facts, weft and warp

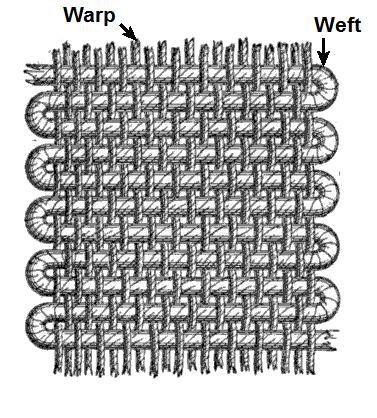

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are interwoven affects the characteristics of the cloth.[1] Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth (warp threads with a weft thread winding between) can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.[2]

Warp and weft in plain weaving

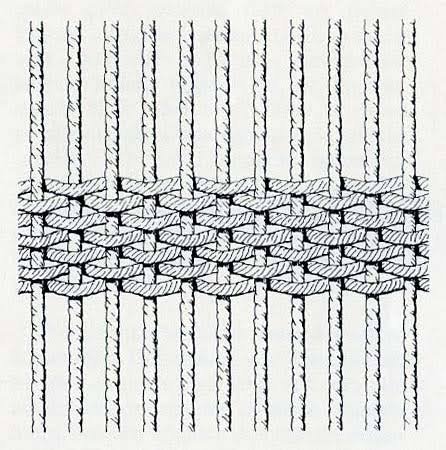

Technically, tapestry is weft-faced weaving, in which all the warp threads are hidden in the completed work, unlike most woven textiles, where both the warp and the weft threads may be visible. In tapestry weaving, weft yarns are typically discontinuous (unlike brocade); the artisan interlaces each coloured weft back and forth in its own small pattern area. It is a plain weft-faced weave having weft threads of different colours worked over portions of the warp to form the design.[2] European tapestries are normally made to be seen only from one side, and often have a plain lining added on the back. However, other traditions, such as Chinese kesi and that of pre-Columbian Peru, make tapestry to be seen from both sides.[3]

Weft faced weaving as used in tapestry

Tapestry should be distinguished from the different technique of embroidery,[4]although large pieces of embroidery with images are sometimes loosely called "tapestry",[5] as with the famous Bayeux Tapestry, which is in fact embroidered.[6]From the Middle Ages on European tapestries could be very large, with images containing dozens of figures. They were often made in sets, so that a whole room could be hung with them.

Kesi

It is a tapestry weave, normally using silk on a small scale compared to European wall-hangings. Clothing for the court was one of the main uses. The density of knots is typically very high, with a gown of the best quality perhaps involving as much work as a much larger European tapestry. Initially used for small pieces, often with animal, bird and flower decoration, or dragons for imperial clothing, under the Ming dynasty it was used to copy paintings.

"Kesi" means "cut silk", as the technique uses short lengths of weft thread that are tucked into the textile. Only the weft threads are visible in the finished fabric. Unlike continuous weft brocade, in k'o-ssu each colour area was woven from a separate bobbin, making the style both technically demanding and time-consuming.

Kesi first appeared during the Tang dynasty (618–907), and became popular in the Southern Song dynasty(1127–1279), reaching its height during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The style continued to be popular until the early 20th century, and the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911–12.

Cartoon: (I like the idea of creating a ‘cartoon’ of a tapestry to accompany the work.)

Christ's Charge to Peter, one of the Raphael Cartoons, c. 1516, a full-size cartoon design for a tapestry

A cartoon (from Italian: cartone and Dutch: karton—words describing strong, heavy paper or pasteboard) is a full-size drawing made on sturdy paper as a design or modello for a painting, stained glass, or tapestry. Cartoons were typically used in the production of frescoes, to accurately link the component parts of the composition when painted on damp plaster over a series of days (giornate).[3] In media such as stained tapestry or stained glass, the cartoon was handed over by the artist to the skilled craftsmen who produced the final work.