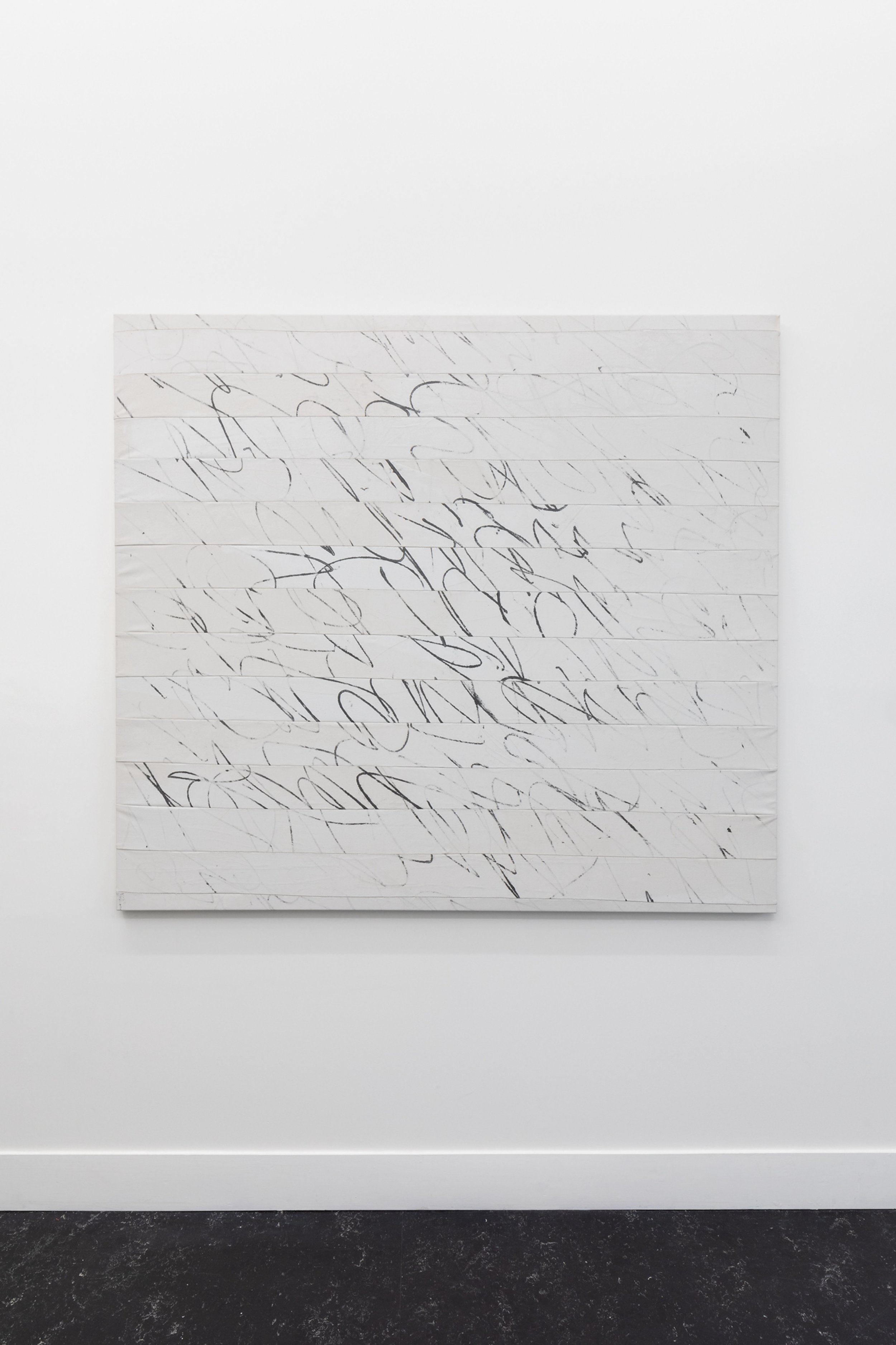

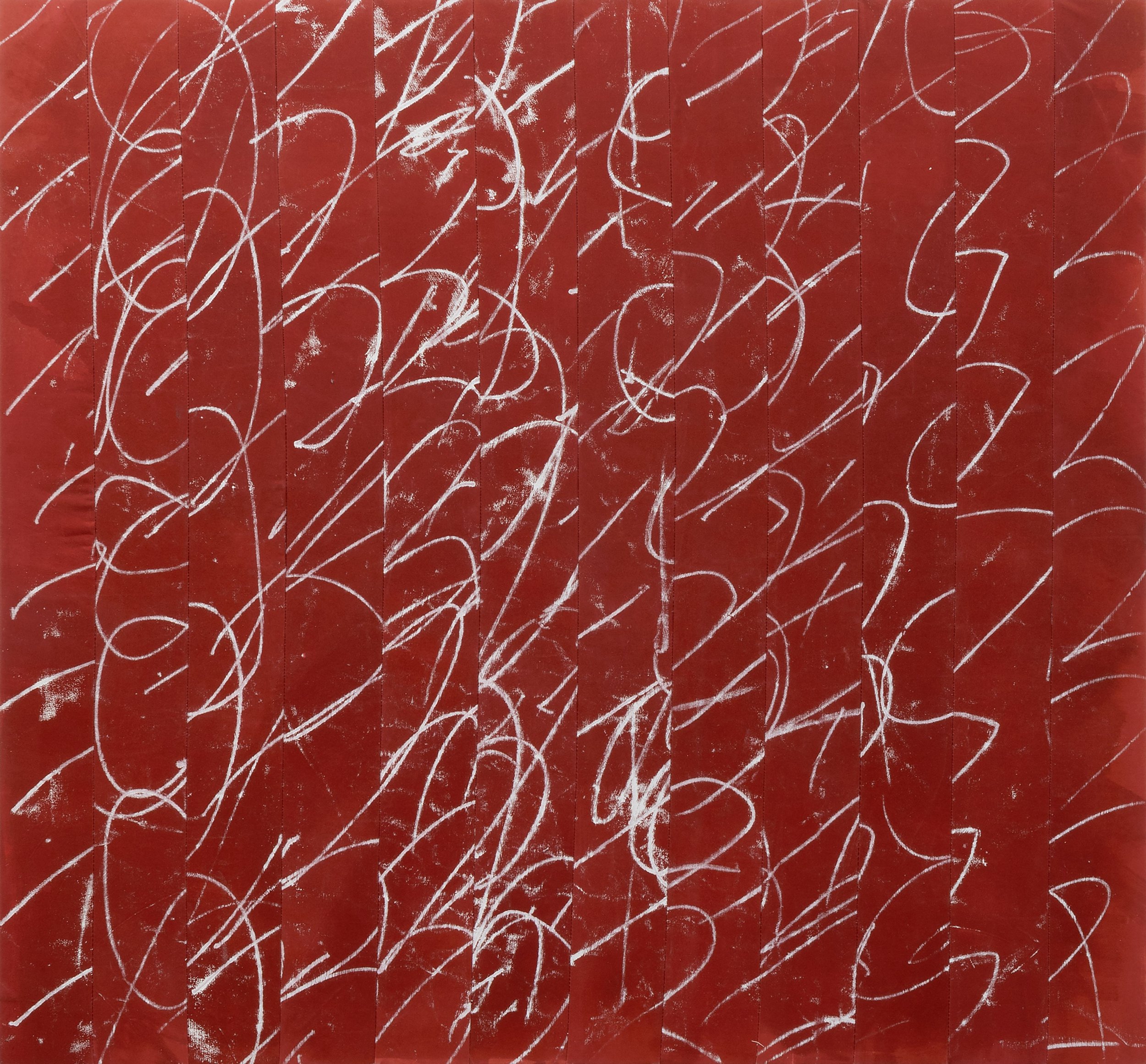

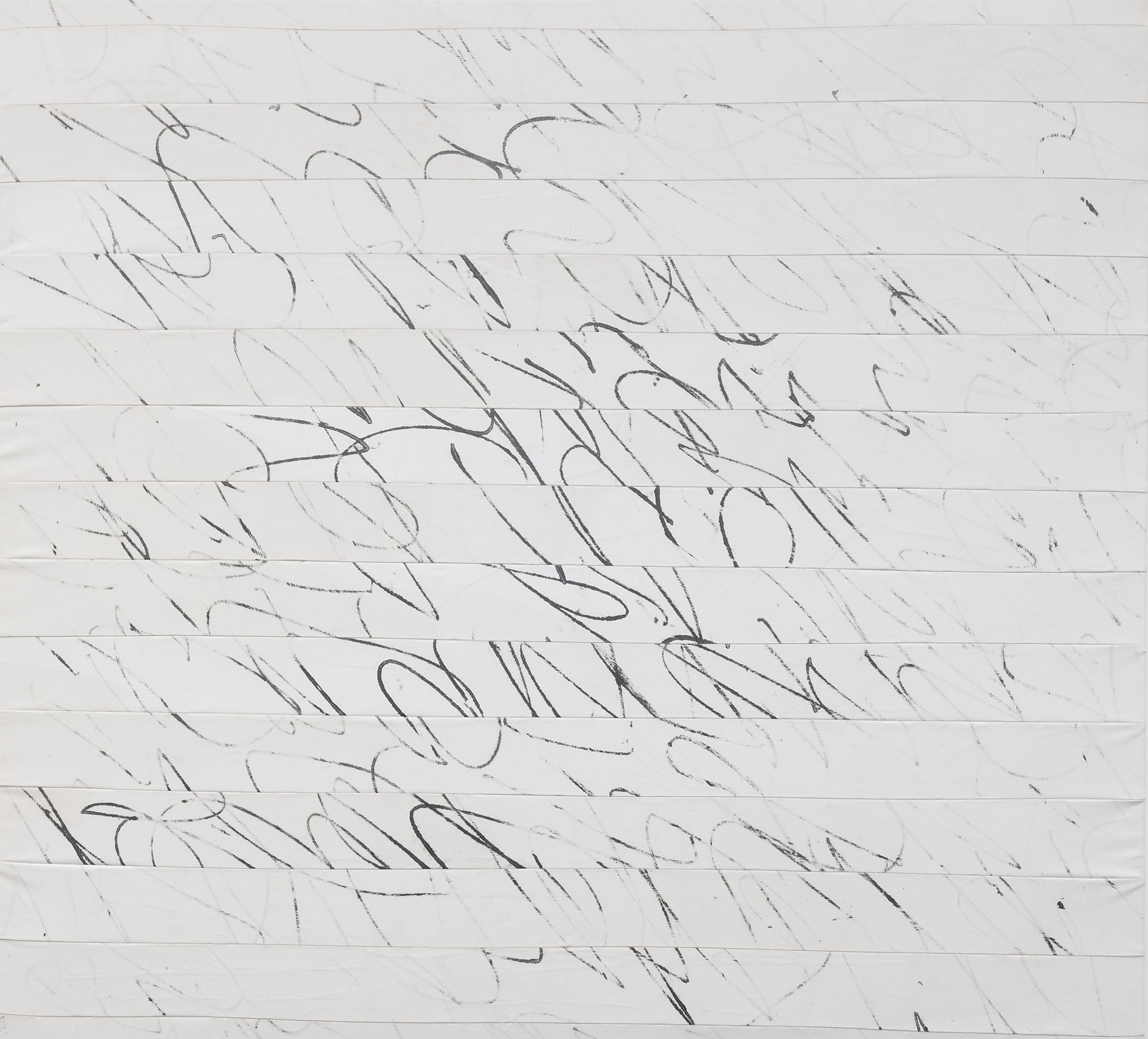

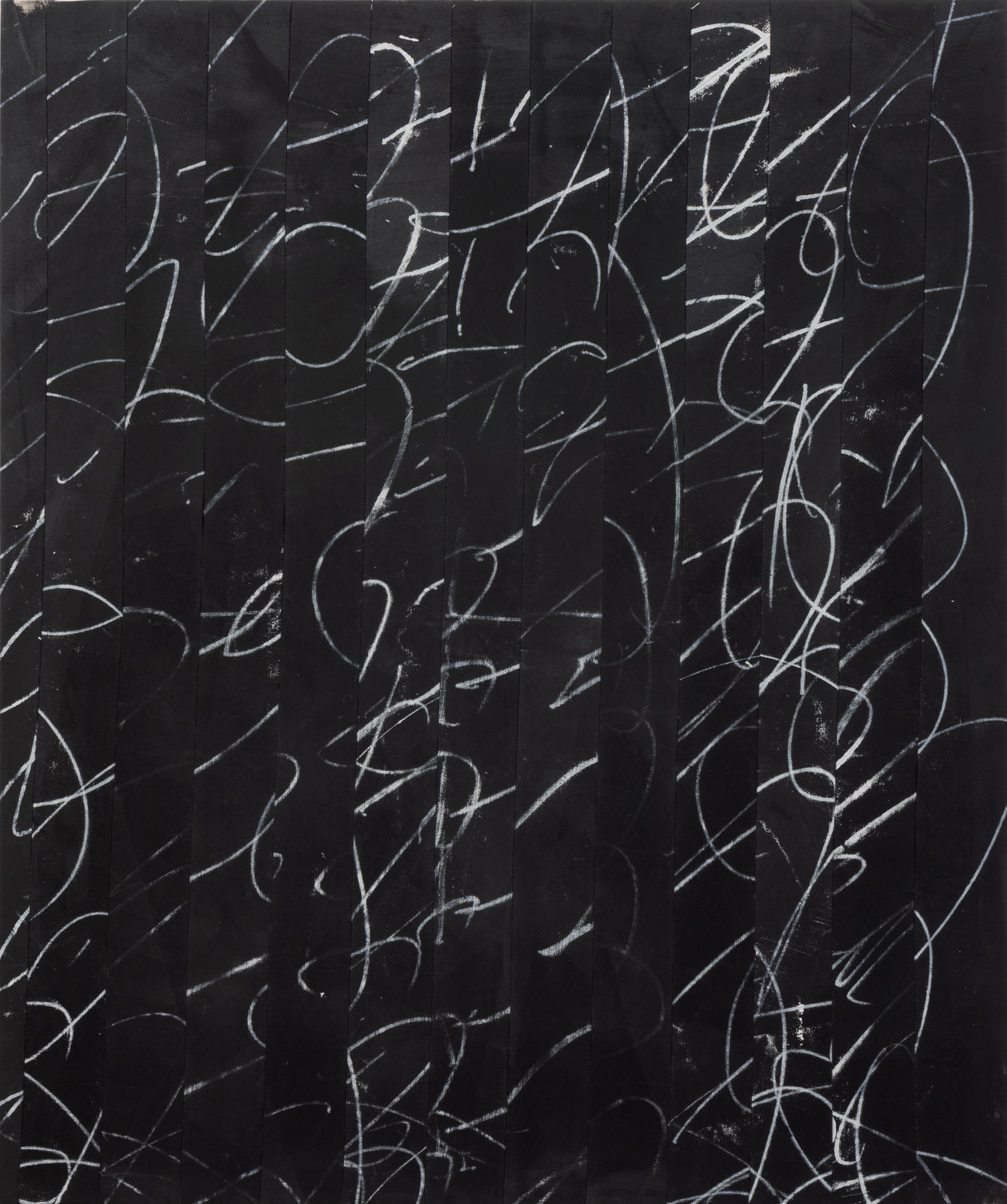

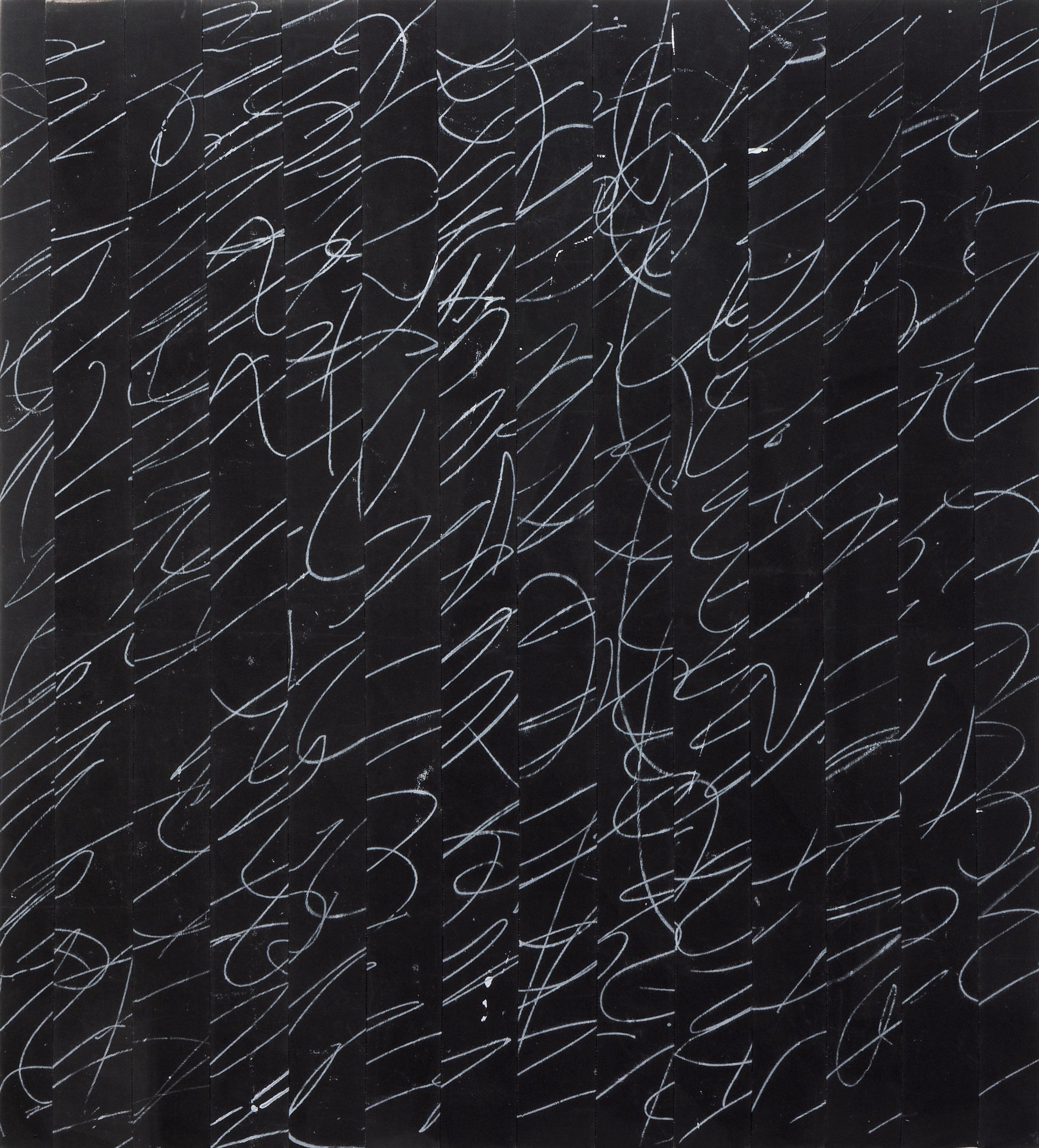

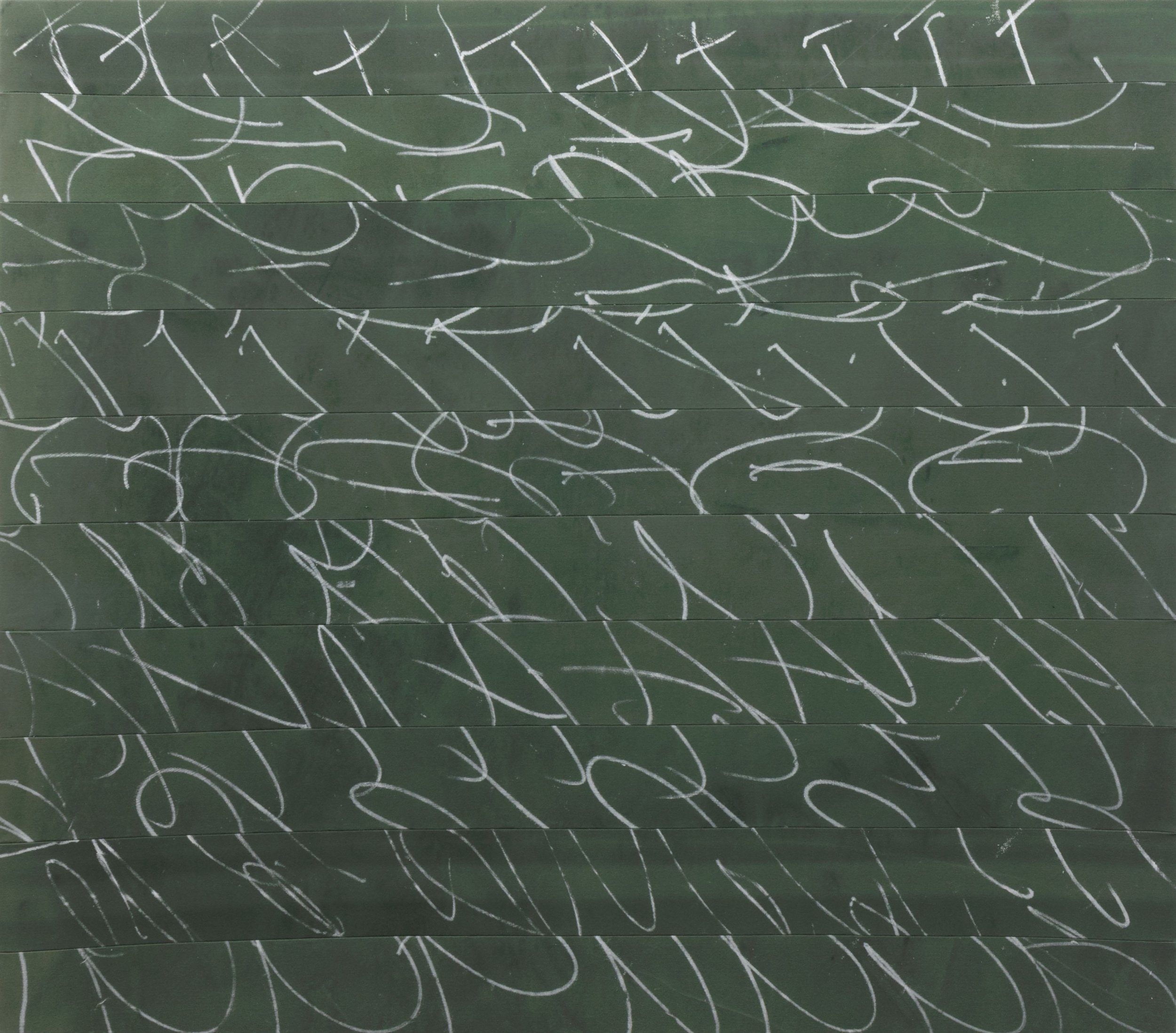

Hugo Koha Lindsay, Mineral Spirit, Envy Gallery, Wellington, 19 June - 19 July 2025.

Installations shots of Lindsay’s show, Mineral Spirit, in Wellington. Text written by Fergus Porteous (a NZ writer and bushcraft/survival instructor).

TAKE AWAYS: ‘reordered and annotated’ script. I am liking the reference to scrip and handwriting as with Twombly. The re-ordering of script on these works, the strip and stripes of only slightly disjointed markings. Like deckchair fabric or flags. I am very interested in how he assembles these strips of canvas as they seem very uniform and flat. When I had a closer look at one of his works at the NZ Art Fair, I couldn’t quite work out if he had sewn them together and then stretched of stretched individually as they were so uniform. Of course, I couldn’t take a peek behind the canvas but when he is next showing at Gow Langsford gallery I might ask one of the gallery staff. The lines are perfectly straight and there is no deviation in flatness across the panel.

TAKE AWAYS: I am reminded of Cy Twombly’s comment that “I never really separated painting and literature because I’ve always used reference.” The close connection or merging of literature and painting. Porteous has written this piece in response to Lindsay’s show and it accompanies the work, on the gallery website without explanation. I like the idea of a short story written upon reflection or visit to a show, the reviewer’s commentary embedded in the words of a story, like when you are given a few key words around which to construct a narrative, similarly, you are given visual prompts in the form of exhibited artworks, to review through a short story. I remember Victoria Chang’s book of poetry ‘With my back to the world’, after she visited an exhibition of Agnes Martin. And Tacita Dean’s book ‘Why Cy?’, a personal reflection and aesthetic connection to the works by Cy Twombly, having spent a night alone with his work in the Menil Collection.

Mineral Spirit (text that accompanies the show written by Fergus Porteous)

Integrity, he said. Somebody in here knows something about this. Integrity, he said again, and swivelled his head as if trying to lock eyes with all fifteen-hundred of us grey uniformed high-socked short-haired schoolboys with his white knuckles gripping the top edge of the lectern and the teaching staff falling asleep on the stage behind him at a special afternoon assembly meant to smoke out which one of us had smeared his own shit all over the science-block-bathrooms for the second time that term. I sat six rows back from the front staring down at the pen-scratched graffiti of the word cunt in the back of the yellow plastic seat in front of me, then looked back up at Headmaster Lyal French-Wright downlit and vulturine in his black academic gown beneath the bannered words Et Comitate Et Virtue Et Sapienta, his voice echoing through us boys, arranged rank-and-file in ascending age hierarchy–four columns on the ground floor, four in the upper gallery–within the cavernous concrete and Kauri brutalist marvel that was Ryder Hall. I sat just behind a long rhombus of sunlight cast in prison stripes across the five rows between me and French-Wright on the stage. Three rows ahead of me, in the middle of this dazzling rectangle, two boys had been stood up for talking, their hair shining in the light like tiny angels as French-Wright continued his sermon on integrity and being a man and coming clean about scatological vandalism as the dust motes floated in the light and he repeated the word integrity four more times. And one of the two standing boys suddenly folded at his knobbly knees like a puppet, sinking into his chair and Lyal French Wright turned furious and said, stand up boy, stand up boy, Stand Up, pointing down like God Himself with spittle on his mouth and his ruddy cheekbones, and the boy woozily swayed while his friend tugged upwards on his school shirt, whispering get up get up get up, but he swayed and overbalanced and hit the ground face first with a slap, and a rumble rolled through the boys, and French-Wright said pick him up, voice booming, pick him up, Pick Him Up. And two teachers dragged him out, his Rugged Sharks squeaking on the linoleum. I walked home through the cemetery in the bitter Southerly that cut through my high socks. Walked home past the spot under the bridge where Chris Van Hoof allegedly got his tip wet, and the graf kids ran out of concrete to spray so they tagged the clay banks overhanging the river. Walked up and over the unfenced remains of Pukewarangi Pā, of Ngati Tū Pari Kino of Āti Awa, where elephant paths meander over the grassy embankments under wilding pines and pōhutukawa. I walked home through the Southerly so distinct that it almost had a smell, or maybe it’s just a temperature memory from its trip up and over the summit of Taranaki, or Egmont, down the scree slopes and over the bush and farmland, between the houses and down the streets, to rattle the flagpoles at the RSA, and whipping the black sand beaches with winkling shards of mica and magnetite, through bleached logs and forestry slash stogged in the wet ironsand below the high tide mark, over the surf to the lines of men, straddling surfboards in head-to-toe black neoprene, rising and falling and gazing not speaking, looking out at the horizon, grateful for the polar wind because of what it does for the barrels at Fitzroy, East End, and The Groyne, throwing spray off the lip like comets’ tails towards the horizon where cirrus clouds spread across the sky like fingers of the retreating sun, as if to warn us of the coming night. The surfers with their backs to the mountain, the Mounga, mournful and dark on his lonely promontory, his Cape – in exile, actually, according to the pūrakau that every child in the region is taught, though our teachers used the word myth, that Taranaki travelled here on hisown from the Central Plateau, fled actually, dragged his corpulent hulk through the whenua, carving a chasm flooded with tears that became the Whanganui river. Fled because he’d been flogged so badly by Tongariro, who stole his woman, his beautiful Pīhama, so when the sun came up Taranaki was fixed where he now stands, forever gazing back at her in anguish, mist clinging to his head like an ancient suspiration, the unwilling archetype of a town that measures against its monicker, or maybe it’s a mantra–Taranaki Hardcore. A mantra for a wild, unbridled masculinity, a kind of bravado, not by yelling or chest beating, but by the abnegation, by a contest of who can speak the least, speak the quietest, while being the hardest cunt, the loosest cunt – men like stone totems, all muscle and sinew, fighting like stags, antler tangled eyes pulsing under the tube lights on Devon Street at 2:00am, and nobody calls the cops because it’s just a scrap, headbutts and haymakers, trudging home with a split lip or a broken orbital, hunting women in town like they hunt wild pigs, with just a dagger for sticking, blood running off the wriggling mess all the way to the elbow, and James Alabaster, a School Prefect who, it was said, went hunting without a weapon and had to drown a goat in the creek with his bare hands, because if it’s hardcore it’s good. A whole town predicated on the utter rejection of the fact that it was built on anything other than a pioneering spirit, a Mineral Spirit, of Capital and Progress; furtherance of the human endeavour. The Energy City, where the beaches are made of iron and silica and titanium – and Oil men come to drill and pump the miasmal remains of vast Eocene swamps and the dead trees of Gondwanaland, the effluvium of incomprehensible catastrophe; and to take it all from Māori without any thanks because Helen Clarke said it’s in the National Interest and then naming the drill sites Kupe, Maui A and Maui B, without irony. And it’s only the expats and the Old-Boys with the good connections who get jobs on the rigs tripping pipe or mixing mud for six figures, for Shell, or Halliburton, or Todd, or Methanex. To continue the taking and the un-naming that began in 1770 when Cook called it Cape Egmont, after Lord of the Admiralty, till the now when every school rugby fixture 1,500 boys are forced to stand to attention in the southerly wind on the shaded Western wall of the gully, staring down the rivals while we perform the haka beneath that cuck mountain, while the head boy paces in front with his pūrerehua humming, wind whistling, and the tackles don’t thud they slap like high voltage shocks and below the sea is sandpapered black and grey, and far above, the lonely mountain is seen as if through glass, blunt topped, leading the wobbled line of the horizon away into another world in the sky.

Fergus Porteous